Celebrating Pacific Languages & Supporting Learners to Master English Literacy

Joy Allcock, M.Ed

August 2025

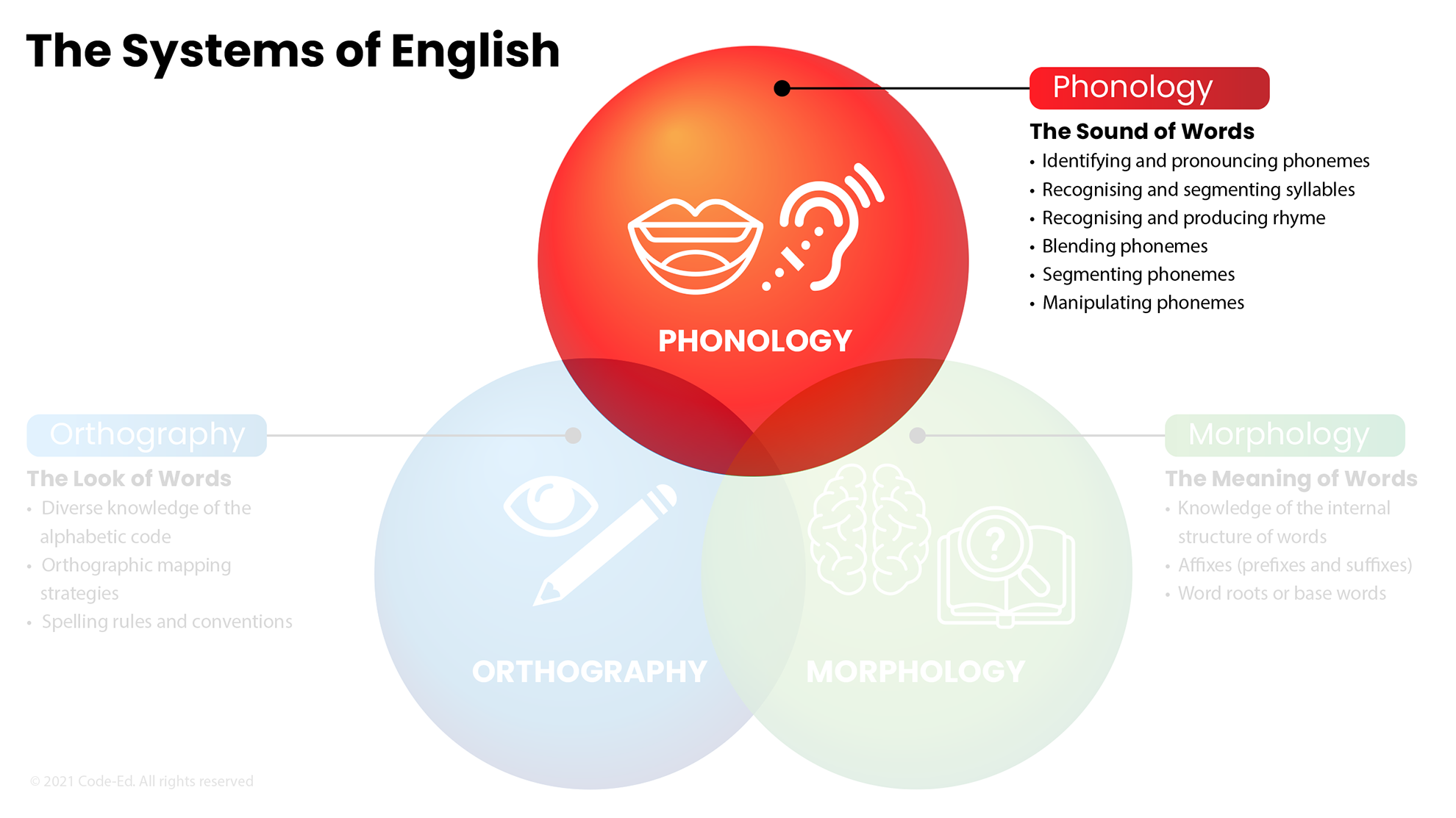

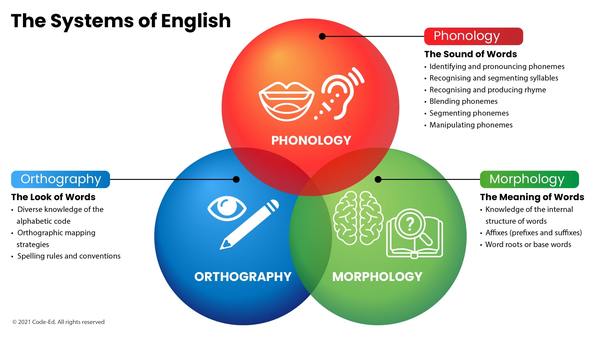

After celebrating Tongan Language Week, it's a perfect time to think about the sound structures of other languages of the Pacific and how they compare with English. Understanding how the sounds of Pacific languages and English are the same and how they differ helps us think about the unique challenges facing children from the Pacific who are learning to speak, read, and write English.

Pacific languages are rhythmic and melodic. This is due to the syllabic structure of words.

Most words in Polynesian languages are multisyllabic. Syllables usually end with a vowel sound, and each syllable is usually made up of two or three sounds. English words by comparison, can be single syllables or multisyllabic. They can end with consonant or vowel sounds and a syllable can be made up of one to five sounds.

The number of phonemes in Pacific languages varies between 13 and 21. English words are made up of 43 sounds (44 for American English). That means there are between 22 and 30 English sounds that people from the Pacific who do not also speak English may never have heard. We learn the sounds of language through hearing words spoken around us thousands of times. Children who are learning to pronounce sounds that they have not been exposed to before, will need many opportunities to hear them pronounced correctly and used in meaningful words.

Many of the sounds that are common to Pacific languages and English are pronounced in a similar way to other English sounds that do not exist in Pacific languages. This can make it difficult for English learners to distinguish between them.

For example:

The unvoiced plosives /k/, /t/, /p/ are easily confused with the voiced plosives /g/, /d/, /b/.

These six sounds are pronounced in a similar way but one group is just air and the other group is voiced.

- /b/ may be pronounced /p/ — pall instead of ball and /b/ might be written p.

- /d/ might be pronounced /t/ — tay instead of day and /d/ might be written t.

- /g/ might be pronounced /k/ — kate instead of gate and /g/ might be written k or c.

There are other 'paired' sounds that might also be confused.

For example:

- /z/ might be pronounced /s/ — soo instead of zoo and /z/ might be written with s.

- /r/ might be pronounced /l/ — belly instead of berry and /r/ might be written l.

To help children learn to pronounce and discriminate between English sounds they have not heard before, use the Sounds of English guide. Click on the phoneme or the sound animal and hear each sound pronounced clearly.

Plosives or stops

Plosives — also known as stops — are sounds produced by a burst of air. The lips and tongue hold back the air for a moment before allowing the sound to burst out. If you hold your hand in front of your mouth, you will feel a puff of air when you pronounce these sounds.

Unvoiced plosives are short bursts of sound with no voice. When pronouncing these sounds, take care not to add a short /u/ or schwa sound. For example, say /p/, not puh. The vocal cords should not vibrate when pronouncing these sounds.

Voiced plosives are short bursts of sound with voice. You can feel your vocal cords vibrating if you touch your throat lightly when pronouncing these sounds.

There are five short vowel sounds in most Pacific languages, and these are most commonly pronounced /ar/, /e/, /ē/, /or/, /ōō/, but in some languages, /u/, /e/, /i/, /o/ /oo/. There are six short vowel sounds in English and with the exception of /e/ they are pronounced differently from Pacific short vowels.

Short vowel sounds

These voiced sounds are made with little bursts of air pushed from the back of the throat. They are not usually heard on the ends of words, although the schwa vowel sound on the end of words can sound like /u/ (pizza).

The five long vowel sounds of Pacific languages are usually pronounced the same as short vowels but are held for twice the length of time, although Cook Islands Māori has different pronunciations for long and short vowel sounds. Long vowels are written with a macron above the vowel letter. There are six long vowel sounds in English which are pronounced like the name of the five vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u) plus /ōō/.

Long vowel sounds

These voiced sounds are pronounced so that they sound like the name of their vowel letter, except for /ōō/. Long vowel sounds are continuous sounds, and some are diphthongs — sounds that start with one vowel sound and end with another. For example, the long o starts with /ō/ and ends with /w/.

There are no consonant blends in Pacific languages, except for some dialects in Papua New Guinea. Pronouncing and segmenting words with consonant blends might initially be difficult for speakers of Pacific languages.

The five vowel letters represent both short and long vowel sounds in Pacific languages although these are generally pronounced differently from English vowel sounds.

Most consonant letters are pronounced the same way in English and Pacific languages, although the letter g is usually pronounced /ng/, and some other consonants might be pronounced slightly differently in some languages.

Each Pacific language has its own alphabet. While the letters are the same as those in the English alphabet, there are letters in the English alphabet that do not exist in Pacific languages. Children learning to read and write English will need to learn to recognise and write these unfamiliar letters and to find out how they are used to write English sounds.

Samoan and Tongan languages both have a glottal stop which is written with an apostrophe. It is considered to be a consonant sound that is caused by briefly obstructing the airflow in the vocal tract, creating a pause between two vowels ( fa’i -banana), or making a shorter sharper sound when it is at the start of a word before a vowel (‘anga - shark).

The Sound Transfer Chart for Pacific Languages shows the sounds that are common to English and Pacific languages. It also shows the letters in each Pacific alphabet. Although some sounds may be common to English and Pacific languages, they may not always be written the way they are in English.

Tips to help support speakers of Pacific languages to pronounce unfamiliar English sounds

-

Allow extra time and practice for Pacific students who are learning English to hear and pronounce the sounds of English that do not exist in their own language

(Use the free Sound Transfer Chart for Pacific Languages)

-

Provide practice pronouncing minimal pairs, working with the sounds that are commonly confused.

For example:

Pronouncing /p/ and /b/ words — pat/bat, pin/bin, pair/bear; /k/ and /g/ words - cot/got, goat/coat, cut/gut; /t/ and /d/ words - din/tin, dot/tot, down/town;/s/ and /z/ words - hiss/his, sip/zip, sue/zoo; /l/ and /r/ words - lip/rip, load/road, lead/read

-

Practice pronouncing and orally segmenting and blending words that contain consonant blends

-

Practice segmenting, then writing words containing consonant blends in Elkonin boxes

-

Use the Sounds of English pronunciation guide to help students hear the difference between similar sounds, and to learn to pronounce the sounds that are unfamiliar.

How Elevate & Evaluate Can Help

If you teach multilingual children, Elevate & Evaluate gives you tools to:

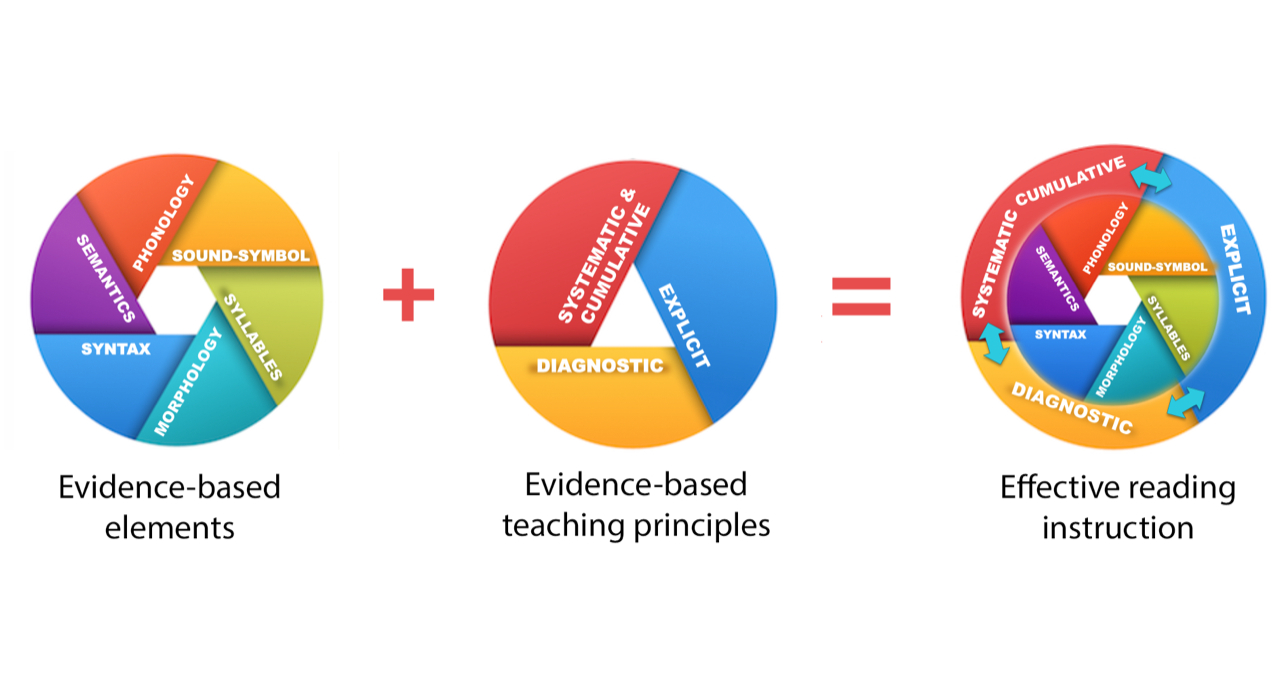

- Build your knowledge of English phonology and orthography

- Access ideas for supporting English learners

- Access ready to use assessments that help pinpoint areas of need to ensure instruction meets learners’ needs

You can equip yourself to meet the needs of all learners by thinking about the languages they speak, the sounds they are familiar with, and the sounds they need to learn to pronounce.

Explore Elevate & Evaluate today