The way humans use speech sounds to create spoken languages differentiates us from other species. Being able to speak allows humans to communicate and transfer knowledge in a rapid and highly sophisticated way. All cultures have spoken languages, and it is the phonological properties of words that differentiates them.

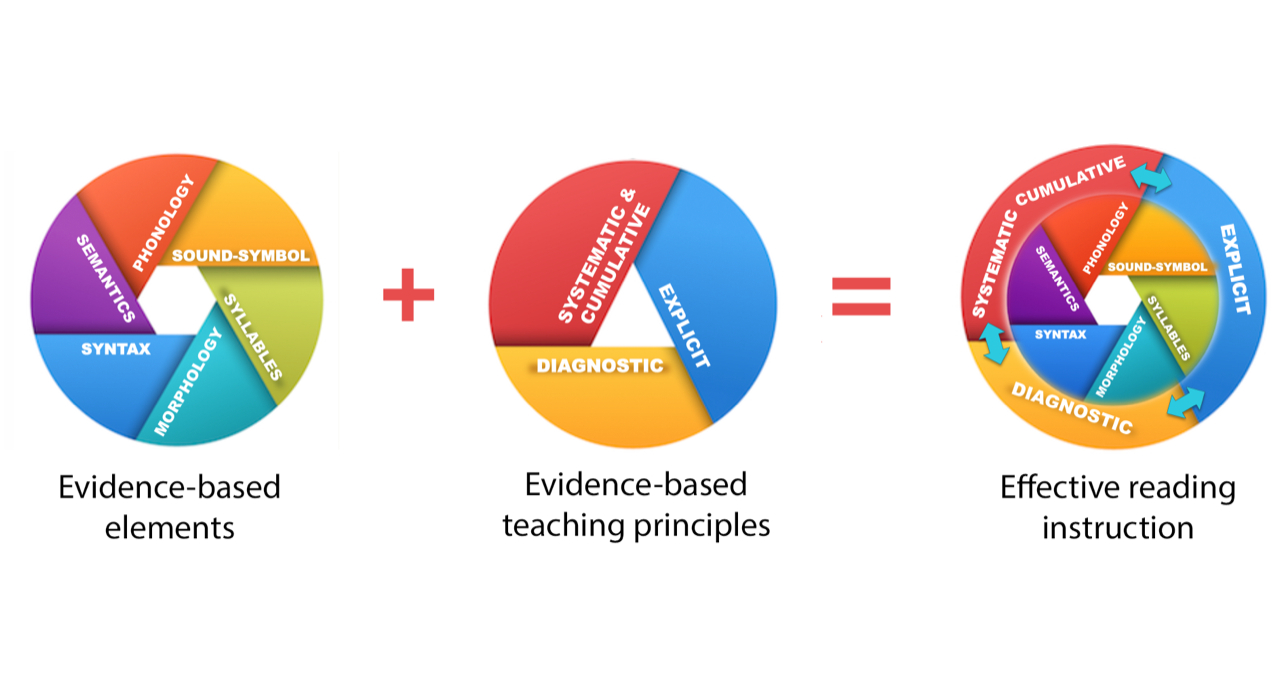

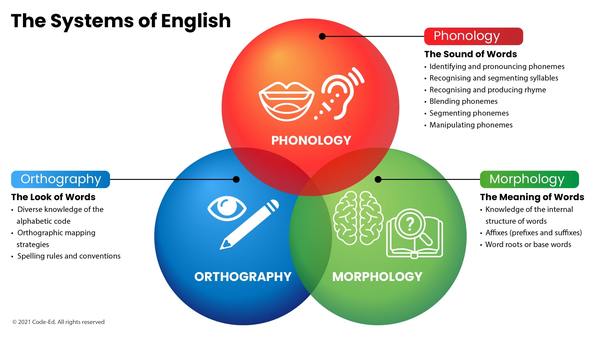

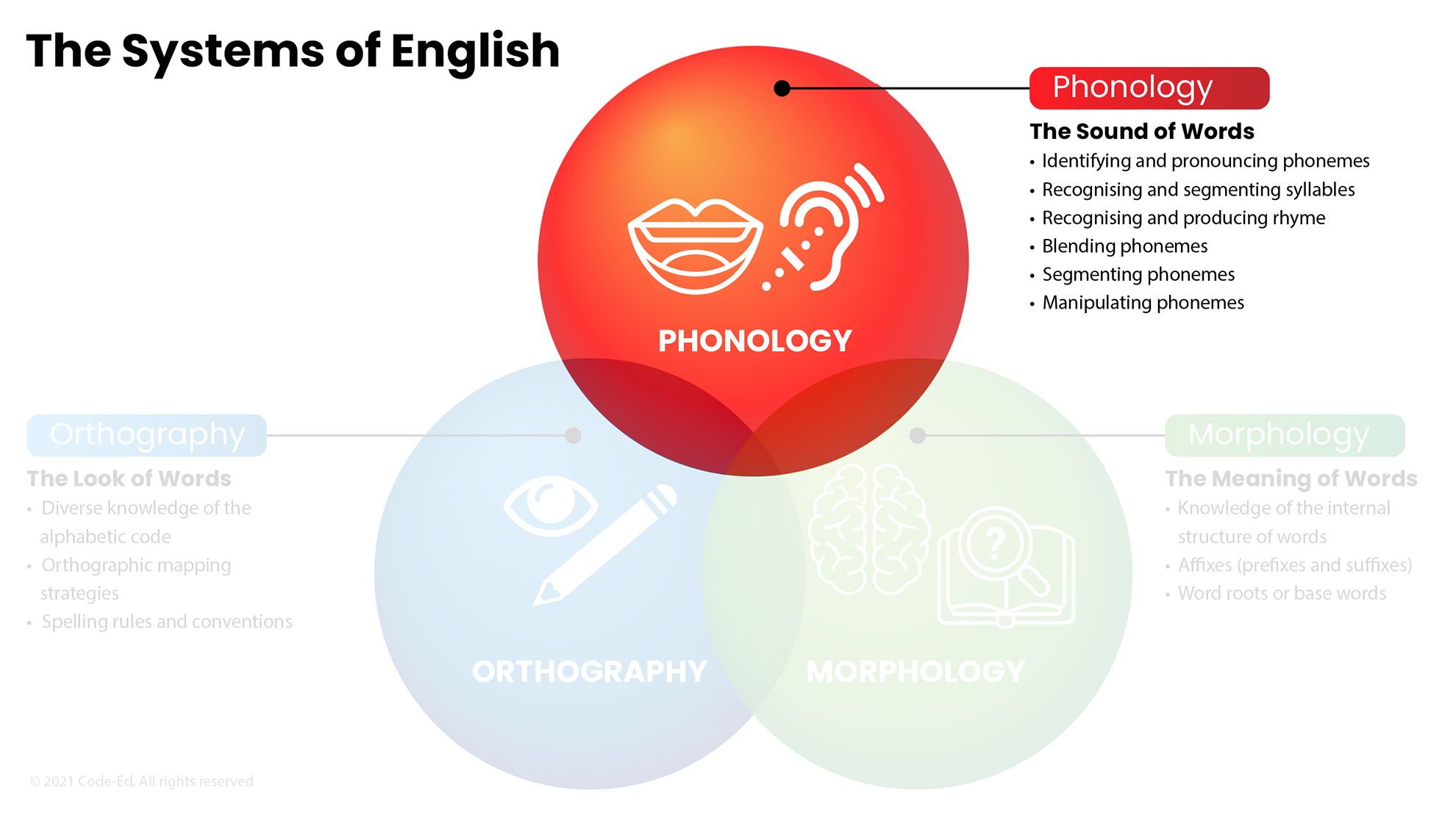

Most cultures also have written languages and many, like English, are alphabetic languages which use alphabet letters to represent the sounds of spoken language. To become efficient and accurate readers, writers, and spellers of English, students need to acquire broad knowledge of the systems that influence the way we pronounce, write, spell, and work out the meaning of words. Understanding the structure of written English is built on knowledge of phonology (the sound system of English), orthography (the writing system of English), and morphology (the meaning system of English).

This article will focus on the phonological system of English, and how knowledge of this system supports learning to speak, read, write, and spell.

The ‘phon’ words!

Phonemes are the individual speech sounds of language.

Although we can learn to pronounce individual phonemes in isolation, they are often pronounced differently and are difficult to recognise inside words and in connected speech. For example, the pronunciation of the /t/ phoneme in English varies in these words, depending on its position and the sounds that follow it. It sounds like /t/ at the start and end of words (toe, top, tickle, put, it) but can sound more like /d/ inside words (stop, stick, matter, settle, water) and in connected speech (ran it over, put it on). A phoneme that can have different pronunciations is called an allophone.

Phonemes have been described as units of sound that we sense in the mind rather than hear or speak.

Phonology is the way in which phonemes are organised and used to convey meaning.

Different languages have different phonologies. Languages also vary in the number and type of phonemes they contain, in the patterns the phonemes form, and in the rules for how phonemes are structured and sequenced. Polynesian languages for example, typically have a small number of phonemes (12 to 15) whereas languages spoken in Northern Europe and Northern Asia typically have more than 40 phonemes. Learning to speak a new language involves learning to hear, produce and pronounce unfamiliar phonemes.

Phonetics is the study of the physical properties of speech sounds and how they are produced.

When we learn new languages with phonemes that are different from those we are familiar with, it is often the phonetic production of the new phonemes that is difficult. For example, English speakers may be able to recognise the rolled /r/ phoneme in Spanish and Italian but be unable to produce the sound easily.

Accents, dialects and stress

Even people who speak the same language can pronounce phonemes differently, which is why there are regional and country-wide differences (dialects) in the way words are pronounced. In some British dialects for example, the short vowel sound in cup might be pronounced /u/ as in umbrella — a ‘cup’ of tea — or /oo/ as in book — a ‘coop’ of tea. In some American dialects the short vowel sound in the word dog might be pronounced ‘dog’ as in pot, or ‘dawg’.

Whether syllables are stressed or not also accounts for different pronunciations of the same word. For example, the er pattern in teacher and farmer might be stressed and pronounced /er/ by one English speaker but be unstressed and pronounced /u/ by another — ‘teacha’, ‘farma’. The stress on syllables can also change the meaning of the word as well as the pronunciation. For example, stressing the second syllable in permit makes the verb (to allow). Stressing the first syllable in permit makes the noun (a written authority to do something).

Developing phonological knowledge

We learn to speak by being exposed to spoken language. Hearing words spoken allows us to develop a mental lexicon — a sort of catalogue or inventory of the words of our language. The more times we hear words and the more words we hear, the greater our listening vocabulary will be. Our listening vocabulary builds a phonological representation of spoken words in our mental lexicon, which is the foundation for our knowledge of phonology.

All the words we have ever heard spoken is called our vocabulary breadth. The words we understand and can use is called our vocabulary depth. The more we hear words spoken, the greater the breadth of our vocabulary knowledge, and the more secure our knowledge of phonology.

[I]t is breadth of vocabulary knowledge, the overall number of phonological representations stored in lexical memory, that is most important in facilitating implicit learning of letter-sound patterns and identifying unknown words in text, not depth of vocabulary knowledge.

Children come to school with wide variations in the amount of language they have been exposed to, but all children bring an awareness of spoken words and the sound patterns of the language they speak, as well as a large bank of words they have heard spoken — many of which they also understand and can use. It is the pronunciation of words — recognising what words sound like — that leads to their meaning.

Readers often use a strategy called ‘set for variability’ when they incorrectly decode an unfamiliar word. They may mispronounce a word because of the diversity in the way a grapheme is pronounced for example, saying shoer for shower. This pronunciation will not match a word in the reader’s spoken vocabulary, but the meaning of the sentence and the closeness of the incorrect pronunciation to the actual word will often lead the reader to self-correct. The success of this strategy for achieving a correct pronunciation relies on the reader’s breadth of vocabulary. Understanding the meaning of the correctly pronounced word relies on the reader’s depth of vocabulary.

When beginning readers apply their developing knowledge of letter-sound relationships to unknown exception words, the resulting partial decoding will often be close enough to the correct phonological form that they will be able to arrive at a correct identification, but only if the word is in their listening vocabulary.

To help children develop phonological knowledge, we need to read aloud to them often, and widely. Read poems, rhymes, simple and challenging texts. Read texts that encourage an awareness of sounds and sound patterns in words — texts that develop both the breadth and depth of vocabulary — the foundations for understanding spoken and written language.

Phonological knowledge and literacy

Alphabetic languages use a sound-symbol strategy to record the spoken word. The phonemes of the language are represented with symbols (letters and letter patterns, called graphemes) which create a written code that allows words to be written and read.

When we write, we learn to record the sounds in words with graphemes. When we read, we learn to pronounce the graphemes, and blend the resulting sounds together to pronounce the word. The phonemes of the language are the building blocks for understanding and using the alphabetic code. An awareness of phonology and phonemes develops from exposure to the spoken word.

Teaching phonological and phonemic awareness

Phonological awareness is an awareness of the sounds and sound patterns in spoken words.

Phonemic awareness is a sub-category of phonological awareness that involves an awareness of individual sounds in words.

A large body of research demonstrates the critical role of phonological and phonemic awareness in literacy acquisition (Fisher et al., 2016; Foorman et al.; 2016). Phonological awareness skills are necessary for the development of letter-sound correspondences and are a strong predictor of literacy learning (Bruck and Treiman, 1990; MacDonald and Cornwall, 1995; Tunmer and Nicholson, 2011).

Because of the importance of phonological and phonemic awareness for the development of literacy, we need to teach it explicitly.

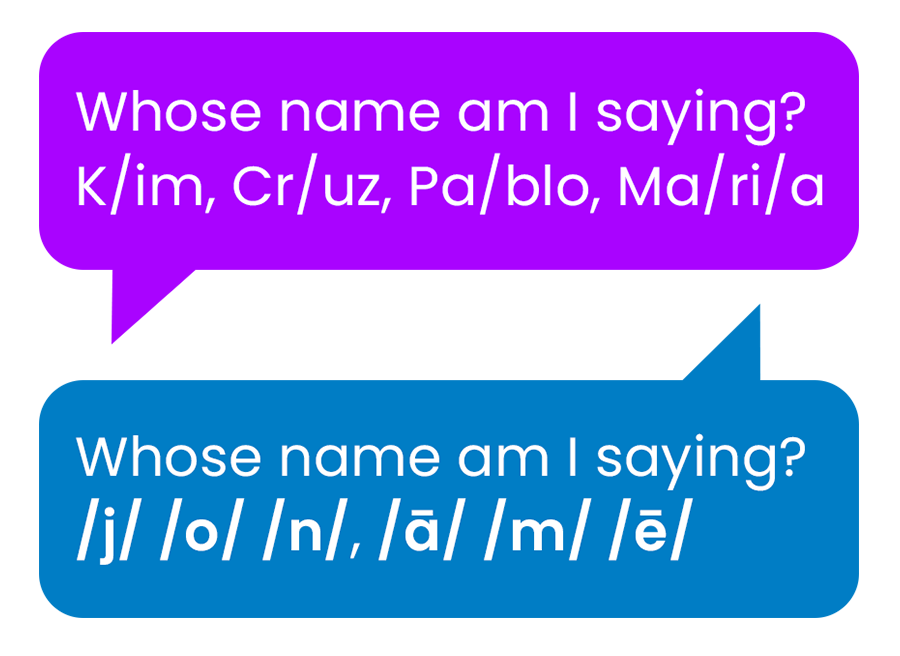

Begin by introducing students to larger segments of speech (words) with which they will be more familiar, and gradually draw their attention to smaller and smaller sound segments. This will prepare them to learn about the individual sounds that letters represent…

We need to teach:

Hearing syllables in words, which involves clapping and counting the syllables in words like duck (one syllable), rabbit (two syllables), umbrella (three syllables), invitation (four syllables).

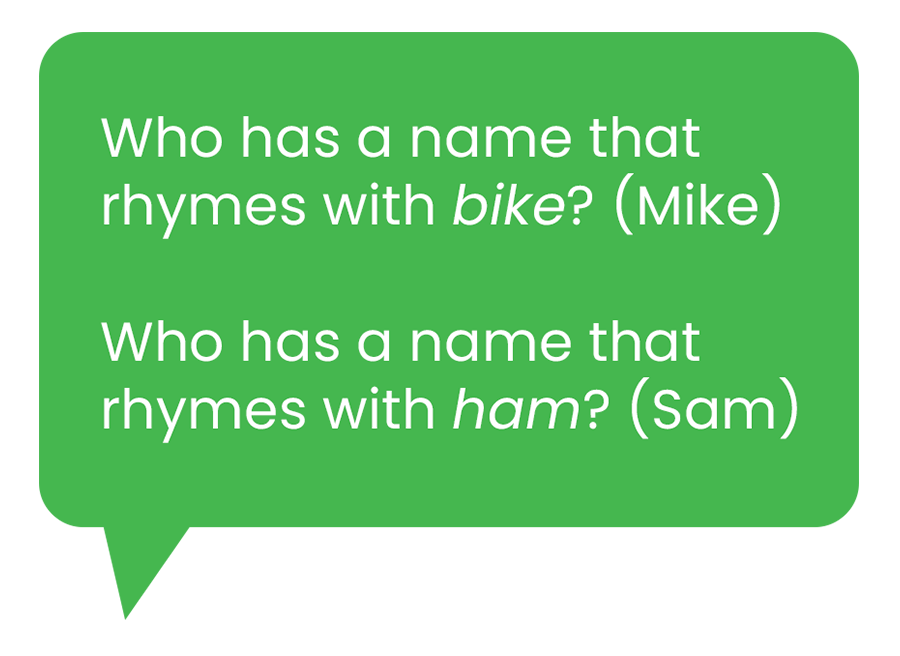

Rhyming, which is the ability to recognise rhyme (which word sounds like mat, man or pat?) and later to produce words with the same ending sounds — the rime (mat — cat, fat, hat, pat, sat, that).

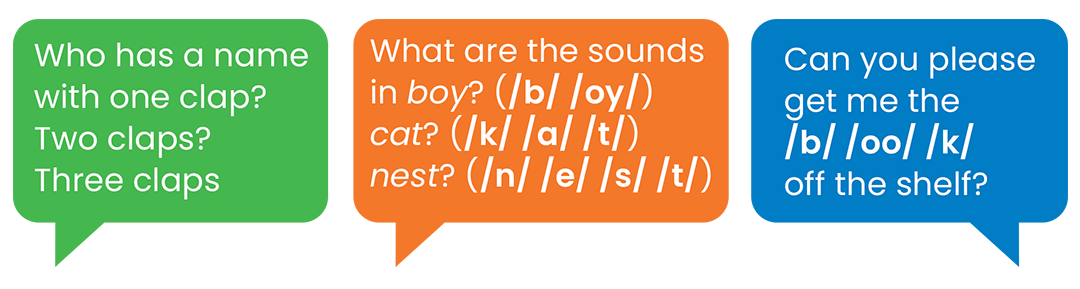

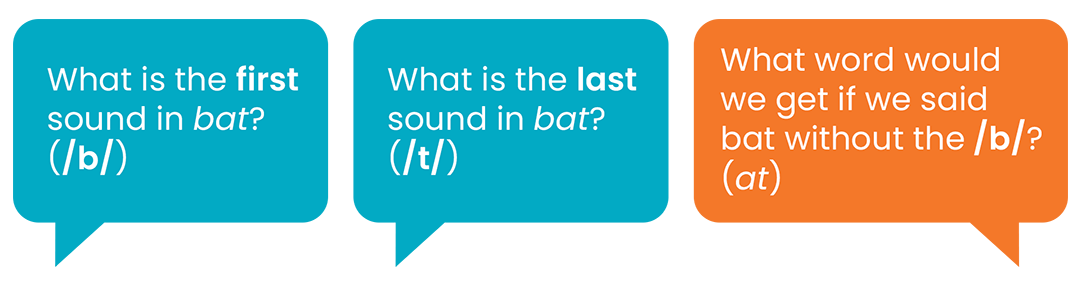

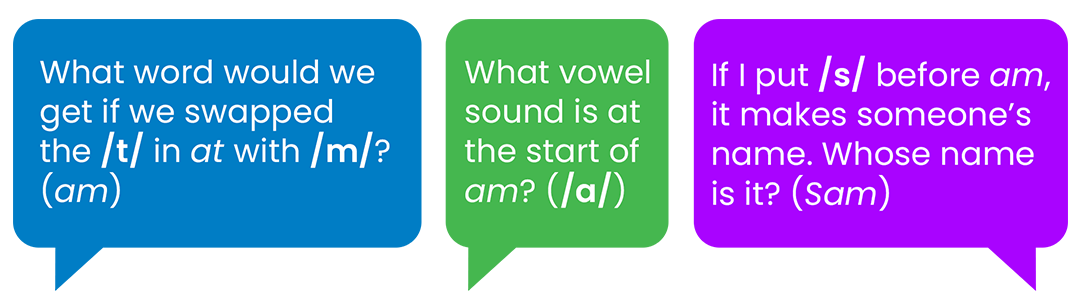

Blending, which is the ability to combine chunks of sounds and individual sounds to make words. It can begin with compound words (grass/hopper, basket/ball), then syllables (hopp/ing, win/dow), then onset-rime (h/ouse, bl/ack), followed by individual sounds (/p/ /ī/ — pie, /h/ /e/ /n/ — hen, /s/ /t/ /o/ /p/ — stop).

Segmenting, which is the ability to break words into parts or sounds. It begins with clapping and counting syllables and progresses to being able to hear, count, and say the individual sounds in words.

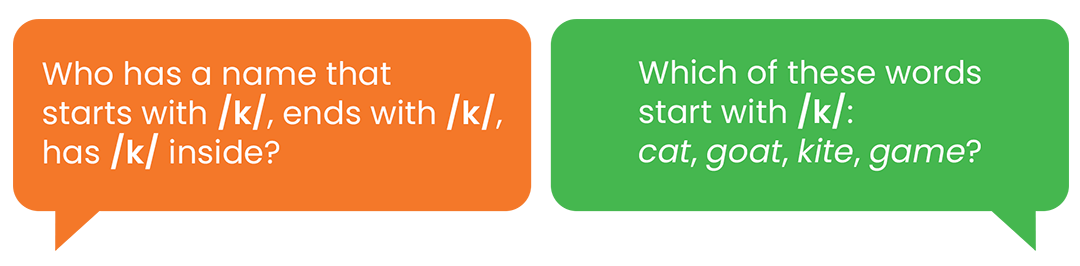

Isolating and manipulating sounds and differentiating between sounds, to help students understand how new words are made and to develop an awareness of the differences in similar sounding words.

Phonological and phonemic awareness skills must be part of early literacy instruction. Some children will need lots of practice to develop them and others will develop them quickly. They are critical for understanding using the alphabetic code to write words they can say, to decode words that they see, and to use the ‘set for variability’ strategy when reading. Knowledge of the phonological system of English is critical for learning to read and write.

References

- Bruck, M., & Treiman, R. (1990). Phonological awareness and spelling in normal children and dyslexics: The case of initial consonant clusters. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 50, 156-178.

- Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy: Implementing the practices that work best to accelerate student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Literacy.

- Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K. ,Coyne, M., Denton, C.A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J. ,Hayes, L., Henke, J., Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- MacDonald, G. W., & Cornwall, A. (1995). ‘The relationship between phonological awareness and reading and spelling achievement, eleven years later.’ Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28 (8), 523-527.

- Tunmer, W.E., & Chapman, J.W. (2011): Does set for variability mediate the influence of vocabulary knowledge on the development of word recognition skills? Scientific Studies of Reading, DOI:10.1080/10888438.2010.542527.

- Tunmer, W.E. & Nicholson, T. (2011). The development and teaching of word recognition skill. In M. Kamil, P.D. Pearson, E.B. Moje & P.A. Afflerbach (Eds.), The handbook of reading research, Vol. 4. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 403-431.

About Code-Ed Ltd.

Code-Ed Ltd. is a New Zealand-based company that specializes in developing educational resources that demystify the way written English works to make it accessible for all teachers and students by explicitly teaching the alphabetic code, the meaning system, and the most reliable spelling rules and conventions of English. Using a linguistic approach developed by author, educator, and researcher Joy Allcock, the Code-Ed resources build a bridge between research and practice, ensuring that teachers have access to evidence-based methods that really work.